Motivators help us understand how leaders approach their role, and the degree of effort they will exert around particular aspects of their leadership role. Companies that understand the similarities and differences of motivation across Asia will have a competitive advantage. They will be able to achieve stronger business performance, by engaging and retaining their leaders better.

Unfortunately, while retaining leaders has become a critical topic for organisations across Asia, little research has explored closely what motivates leaders in Asian countries. The research studies that do exist typically focuses on a single country and measure different types of motivators which makes it very difficult to do cross-country comparisons. This study, by looking at differences in motivators across countries, provides a better insight into what is unique and common to the leaders across the geographic boundaries. Thus addressing this topic became an important objective for us at PDI Ninth House, a global leadership solutions company with over 40 years of experience in understanding leaders.

In comparing the responses from hundreds of leaders operating in China, India, and Japan in comparison to those from the US, some interesting trends emerge. In this article we will highlight some of the more interesting and useful trends that can guide organisations in how to most effectively optimise and expand their leadership talent across Asia.

Key Findings

The four most relevant highlights of the research findings for organisations in Asia are that:

- Commonalities across Asia include the “achievement” and the “balance” motives.

- Level of compensation, while important, does not factor as one of the top motives

- Apart from “achievement” and “balance,” there are significant motivational differences across Asia.

- Leadership motivation appears to not just be a result of — but also a reaction – to culture.

About this Research

The survey used in this research study asked managers to indicate out of a list of 19 motivators which five motivators were most important to them. These 19 motivators can be classified into a taxonomy of seven core sources of motivation that drive us in a work context. These seven core motives are:

- Achievement: Driven to personally accomplish significant goals

- Autonomy: Driven to act independently and express creativity

- Mission: Driven to work in environments that have a broader and relevant purpose

- Power: Driven to seek out opportunities for recognition, prestige, authority and/or control

- Relationship: Driven to seek out opportunities to build strong relationships and/or be of service to others

- Balance: Driven to seek work environments that place equal emphasis on nonwork activities

- Security: Driven to seek work environments that provide security and stability

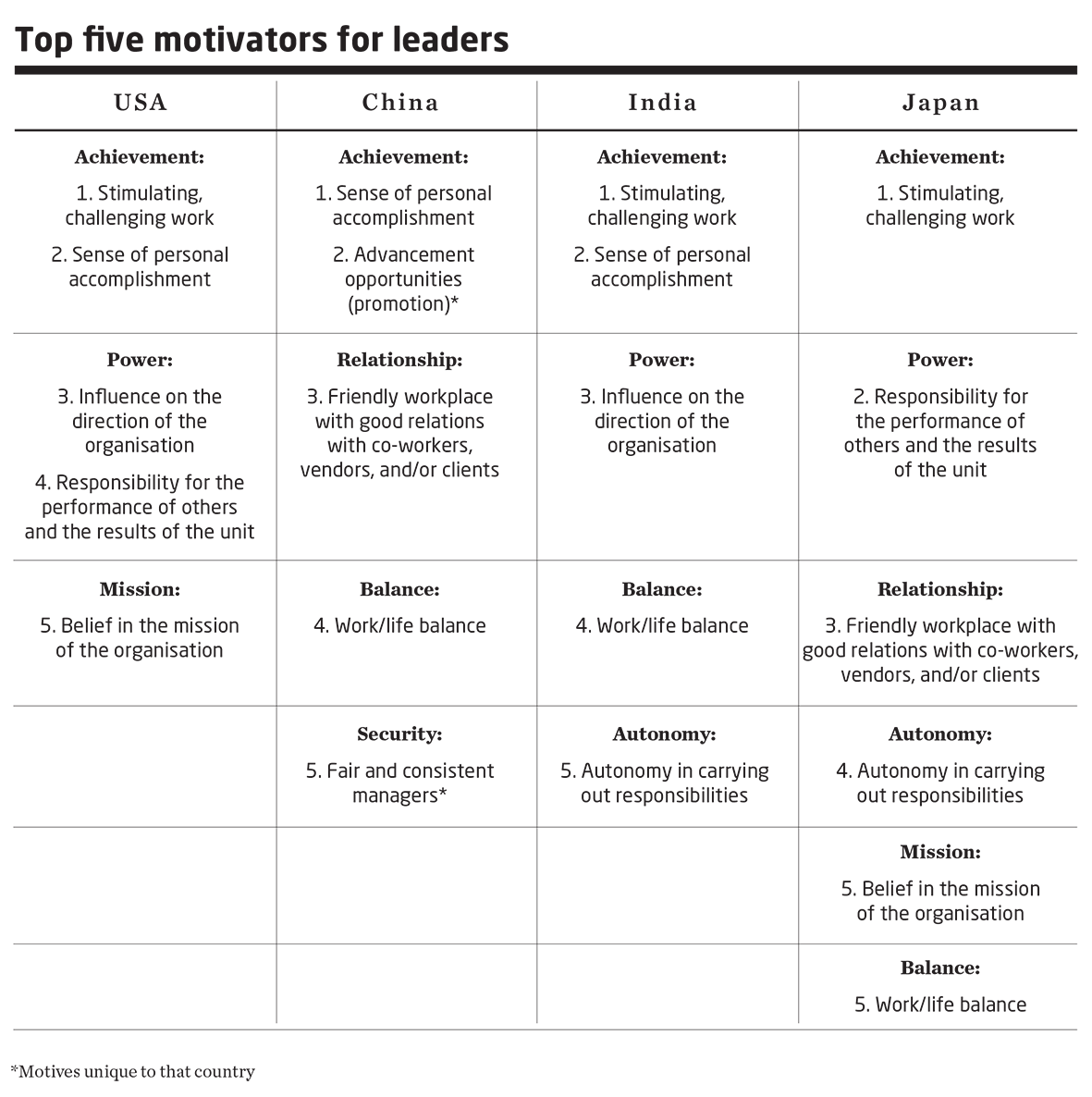

The top five motivators for each country, with their associated core motive, are:

Click on the image to enlarge.

Common Top Motivators – Achievement and Balance

What tended to be a top motivator for leaders across all four countries was the work itself. Leaders are looking for roles that provide challenge and a sense of accomplishment. This is good news as it suggests that providing challenging assignments can be an effective tool to drive motivation across diverse cultures. In addition, work/life balance was chosen as one of the top five motivators in all three Asian countries, but not the US. This suggests that, while leaders appreciate challenging work, they also value time for pursuits outside of work. Beyond this however, the other top motivators varied considerably by country.

Not a Top Motivator - Compensation

One of the more interesting findings is about what is not on the list. Specifically, while compensation is often a tool used to attract or retain talent, monetary compensation was not on the top five motivators for any of the countries. Its rank was between 6th and 8th among the 19 possible motivators. This is consistent with other research that shows that compensation is a poor motivator of sustained effective performance. Compensation may often be a secondary-level motivator that is supporting a much more important motivator for the leader such as providing a source of status and power or allowing them to engage in enjoyable activities during their personal time. . In these cases, it is far more effective for organisations to consider how to address the more primary motivators for the leader.

Motivation in US leaders

US leaders tend to be heavily driven by individual accomplishment (achievement) and the opportunity to influence the direction of the organisation (power), as well as belief in the organisation’s mission (mission). They are motivated by challenging work, having responsibility for others and being in a place where they believe in the mission of the organisation. The top two motivators, stimulating work and influence on the organisation, seem to be remarkably stable over time as the Inc. magazine found the same two motivators ranked No. 1 and 2 in their 1989 survey of US managers. Relationships, balance, and security are absent from the top five for US leaders.

Motivation in Chinese leaders

In China, we see the biggest contrast with those leaders in the US. This may make it all the more challenging for US leaders operating in China, and vice versa. In China, in addition to the common motives of stimulating work, the key motives include a focus on “relationship”, “security” and “balance” where individuals are in a friendly environment that provides a work-life balance, fair managers and the opportunity for status advancements through promotions. Absent from the top five in China is “power.” This creates an interesting dilemma for organisations: Leaders may be less focused on the opportunities to lead and influence the organisation as they are on assuring their own comfort and status. However, it could also be argued that in China, leaders recognize the value of harmony and good relations as key to being a successful leader which is consistent with Confucian principles.

In China, we see the biggest contrast with those leaders in the US. This may make it all the more challenging for US leaders operating in China, and vice versa.

This concern for a friendly workplace is shared with Japan. However at this point, Japan differs from China almost as much as the US. The Japanese managers share with US leaders an interest in challenging work and taking responsibility for the performance and results of others and the importance of a belief in the organisation’s mission. Yet they also seek greater control over their work, including both autonomy and a sense of work-life balance. Overall, Japanese leaders show the greatest diversity in motivators and hold motives where there is a potential for conflict. For example, it can be a challenge to seek autonomy in one’s work while also seeking responsiblity for the performance of others while also assuring friendly relationships. In addition, one’s efforts to have stimulating and challenging work can conflict with one’s desire for work/life balance, a dilemma shared by Indian managers.

Motivation in Indian leaders

As in Japan, leaders in India show a desire for autonomy within a culture that is more conservative and one that demands compliance within a hierarchical environment. The Indian leaders also show a unique mix of motivators that causes them to share particular motivators with each of the other three countries. When compared against different profiles of leaders that have been studied by PDI Ninth House, the profile of an Indian leader resembles that of the younger generation of driven high potential emerging leaders where the focus is on gaining influence and power while having the opportunity to have autonomy and maintain a sense of work-life balance to support other interests.

An Evolving Picture on Work-life balance

Finally, another consistent finding across countries is that while work-life balance was a key theme for the Asian countries, this does not equate to having a stable job with little change, as this motivator was consistently the least likely to be chosen as one of the top five, across all four countries. This is a change from the past for many Asian countries that believed in the concept of the “iron rice bowl” and lifetime employment. Job stability and security are not key motivators for Asian leaders. Generally leaders in Asia are typically looking for work that is stimulating and provides promotion opportunities where they also have the space for the other aspects of their life like family and friends.

In Conclusion

Overall, some interesting lessons are learned from focusing on motives. In this case, we see alignment across countries in that leaders want rewarding and meaningful work and that compensation is not a primary motive, and stability is at the bottom of the list. Yet the differences across cultures begin to spread significantly from that point and can reflect both an influence of culture and a reaction to culture. For example, work-life balance is emerging as a key motivator in cultures that have otherwise been seen as extremely work-focused. This desire for motivators different from traditional local companies may reflect the bias in our sample on leaders working for multinational companies. However it also attests to the fact that the wave of leaders coming in today’s organisations may have very different approaches to motivators from those in the past.

Much can be learnt by understanding the motives of one’s leaders. It is also important to note that, while it can be of value to make national-level observations, each individual leader’s motivations are derived from personal experiences and thus it is important to understand the motivation of each leader, rather than rely on generalizations. For example, in this study, no single motivator was chosen by more than 60% of managers in a particular Asian country. It is important for an organisation to learn of the unique personal motivators for each of one’s key current and future leaders. By better understanding the different varying elements that comprise motivation and how one’s culture and experiences can affect what is seen as motivating, organisations can make more informed decisions on how to motivate the type of key leadership talent which will, in turn, drive the success of their business.

The authors and HCLI would like to thank Dr. Joy Hazucha and her team for providing the original research data and her continual guidance throughout this project in her role as Senior Vice President of Leadership Research and Analytics for PDI Ninth House.

This article was first published in HQ Asia (Print) Issue 04 (2012).