What happens in China, India and Indonesia – Asia’s three most populous countries – will go a long way towards determining the global economic environment. For anyone interested in doing business in or with these countries, understanding the nature, motivations and drivers of their business management leadership has never been so important.

China

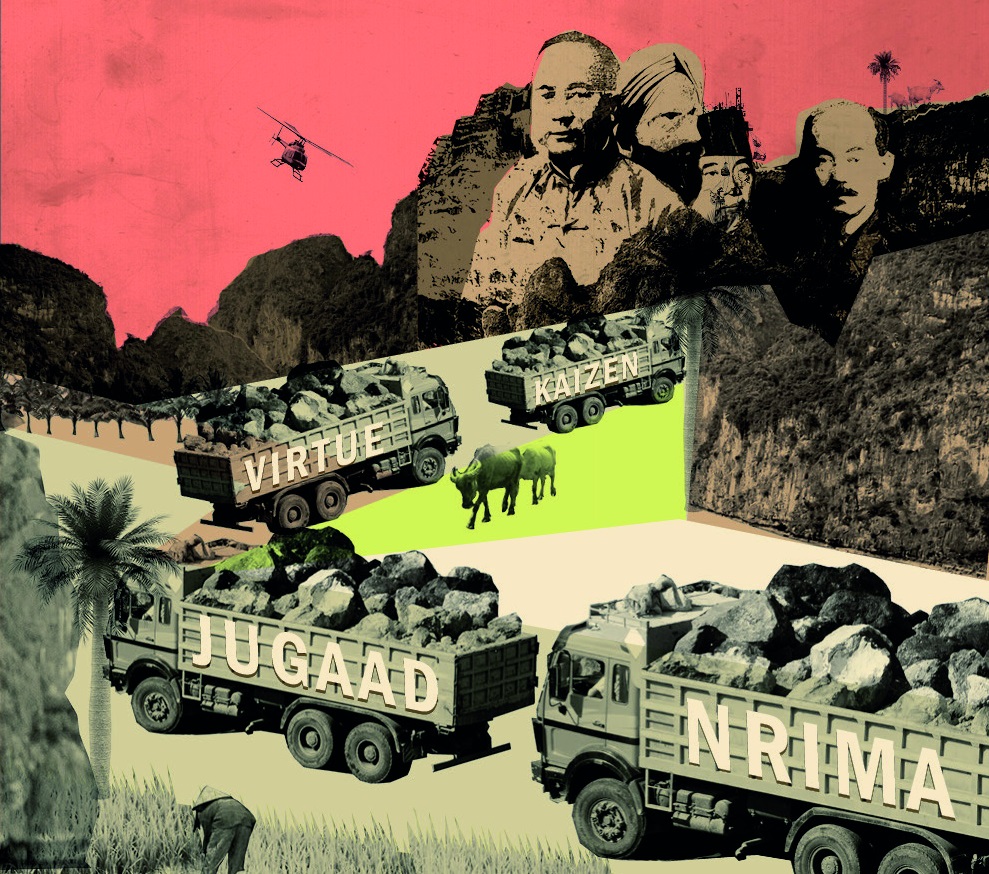

Engage any business leader that is knowledgeable about Chinese leadership and terms such asguanxi and ‘saving face’ inevitably pop up. While these terms are well established, a relatively new concept has emerged in Chinese business management: ‘virtuous leadership’. A virtuous leader is defined as demonstrating personal integrity, self-discipline and the willingness to make decisions based not only on personal benefits, but also for the good of employees and the local community.

In a 2011 study of how Chinese managers perceive Western theories of leadership, virtuous leadership emerged as the most highly rated by Chinese managers, with authoritarian leadership the least highly valued. Traits of the virtuous leader include integrity, self-discipline, the honouring of promises, adherence to principals and maintaining high levels of excellence.

For Chinese managers, the role of a leader – virtuous or otherwise – is critical, not only to the success of the organisation, but for the development of the Chinese economy as a whole. However, the idea that virtuous leaders are the ideal candidates to drive Chinese economic development appears somewhat contradictory.

In 2012, China ranked joint 80th out of 176 countries on Transparency International’s annual corruption index (the index ranks countries based on surveys of business perception of how clean their public sector is). This perception tallies with a 2013 poll by a government-operated newspaper that placed fighting corruption as the Chinese public's biggest concern.

If corruption continues to be perceived as a prevalent issue amongst China’s business and political leadership, can Chinese managers really place so much emphasis on virtuous leadership?

In HQ Asia’s opinion, there are two ways of approaching this apparent dichotomy. On one hand, the rejection of authoritarianism in favour of virtuous leadership can be seen as a desire on the part of Chinese leaders to reform both the public and private sector. China’s President Xi Jinping identified fighting corruption as a priority in his first speech as leader, lest corruption damage the development of the nation and legitimacy of the party.

When discovered, corrupt political officials and businesspersons have been severely dealt with. Real estate magnate Zhou Zengyi was once estimated to be worth US$320 million, but is currently serving a 16-year prison sentence for corruption, while retail tycoon Huang Guangyu, once the richest man in China, was sentenced in 2010 to 14 years in prison for bribery. Former Chongqing police chief Wang Lijun was sentenced to 15 years for abuse of power and corruption, and two former vice-mayors of Chinese cities were executed in 2011 for taking millions of dollars in bribes.

In the private sector, Chinese firms are increasingly adopting ethical practices. Prominent Chinese business leaders, such as Wang Shi, CEO of China Vanke, China’s biggest residential real estate developer, have emerged as champions of good governance. His philosophy of placing ethics above commercial interests saw China Vanke named ‘China’s Most Esteemed Enterprise’ on seven occasions by industry peers and academic bodies.

On the other hand, Chinese leaders could view bribery as a necessary evil. In this reading, they are prepared to accept it, as long as organisations, local communities and the national economy also benefits. Ren Zhengfei, founder and President of Huawei, the world’s largest telecommunications equipment maker, could be seen to exemplify this seemingly contradictory stance. Huawei creates over 110,000 jobs in China alone, and generated revenues of over US$35 billion in 2012.

However, Ren and Huawei have been accused by Western competitors of stealing product designs and collaborating with the Chinese government in industrial and military espionage.

The negative publicity has seemingly done no harm to Ren or Huawei’s standing amongst his peers – both at home and abroad. China’s Commerce Ministry dismissed the allegations as ‘groundless accusations against China’, and Ren continues to be showered with international acclaim, including multiple nominations in Time Magazine’s 100 Most Influential People.

Whether Chinese business leaders genuinely embrace the concept of virtuous leadership could be a determining factor in shaping Chinese leadership. The traits of the virtuous leader are highly rated, but whether such a leader is best suited to an oft-pragmatic business environment will be interesting to observe.

India

India is somewhat of a paradox. It has seen startling economic growth over the past two decades, but it has achieved this against a backdrop of stifling bureaucracy, rampant corruption, scarce resources, patchy infrastructure and an enormously diverse population with low per capita income.

In the face of these issues, India’s economic development has sometimes been attributed to the persistent ability of Indian workers to innovate and solve problems. In Hindi, this ability is described as jugaad, which roughly translates as improvisational solutions. The jugaad methodology uses a trial and error approach that is rooted in a culture of scarcity and constraints.

Jugaad in practice Various Indian firms have used the methodology and practices of jugaad in refining their business models. Adaptability and innovation are the hallmarks of this approach to problem solving. Yes Bank The Indian private bank introduced a mobile payment solution that allows people to transfer money via mobile phones, without the need for a bank account. In India, with around 900 million people have mobile phones, Yes Bank leveraged India’s extensive mobile telephony infrastructure in order to reach the estimated 600 million people without bank accounts. Tata Motors The Tata Nano is the world’s cheapest car. To achieve this, Indian automotive MNC, Tata Motors constantly adapted and refined its business model. From switching construction sites to a more investor-friendly state, to changing distribution models and sales techniques, Tata Motors looked to implement changes quickly and efficiently. Despite the low price, sales of the Tata Nano were disappointing. To facilitate take-up, Tata recently announced an innovative sales plan: customers had the option of paying with their credit cards and driving out with a Tata Nano on the same day.

In the 2010 book The India Way: How India's Top Business Leaders Are Revolutionizing Management, the authors – Peter Cappelli, Harbir Singh, Jitendra Singh and Michael Useem – argue that India’s achievements are due to its corporate leaders and their unique management style. For Indian leaders, argue Cappelli et al, an organisations’ most important goal is not maximising shareholder value, but serving a social mission and creating added value for society.

In The India Way Indian leaders are shown to be warm, considerate and nurturing towards their subordinates, and are committed to the development of their staff. However, Indian leaders will only provide such consideration upon the subordinate demonstrating they can and will continue to perform well.

This nurturing aspect of Indian leaders can be seen in Vineer Nayar, CEO of HCL Technology. He set up an online forum called U&I through which he could interact with the company’s 72,000 employees worldwide. Nothing was censored on U&I, and Nayar openly discussed his own need for growth. To encourage transparency and set an example for other employees, Nayar posted his own ‘360-degree feedback’ scores – performance evaluation models that incorporate assessment from superiors, peers and subordinates. By introducing initiatives and policies that empower and reward employees that take risks and show innovation, Nayar exemplifies the Indian way of leadership.

This alchemy of nurturing and task-oriented qualities, as well as a jugaad or improvisational approach to innovation, is arguably what makes Indian leaders an exportable resource to the global market. As Asia continues to grow in affluence, India’s business leaders should increasingly gain prominence on the global stage.

Cultural concepts Guanxi (commonly translated as ‘connections and relationships’) - A central tenet of Chinese culture dating back to the Confucian emphasis on reciprocal behaviour, guanxi creates access to better opportunities, and enables entry into the inner circles of trust of both employees and business leaders. Jugaad (commonly translated as an ‘improvised arrangement’) - The increasingly flexible Hindi word can be used to apply to a locally made, improvised motor vehicle, often no more than an engine on a cart; a workaround approach to a logistical or bureaucratic problem; or an innovative management concept to problem-solving. Nrima (commonly translated as ‘acceptance’, or sometimes ‘passive acceptance’) - A Javanese concept of self, nrima enables individuals to accept setbacks without undue disappointment or emotion. There are a number of theological and philosophical explanations to nrima, ranging from the collectivistic Javanese culture to acceptance of divine predestination.

Indonesia

The economic potential of China and India has been well documented over the last decade, now Indonesia looks set to join them as a regional economic superpower. With a population of over 240 million – the world’s fourth largest – and GDP growing at an annual rate of 6.5% according to the World Bank, the archipelago is fast attracting interest from foreign governments and private organisations alike.

However, Indonesia’s status as one of the world’s rising economic giants perhaps stands in stark contrast to the often-humble values of its people. One of the key traits of Indonesian culture is nrima, a Javanese concept that is broadly defined as an acceptance of present circumstances.

Often misinterpreted as indicative of apathy or a lack of ambition, nrima is regarded in Indonesian culture as a positive, resilient trait. It is a trait that many Indonesians, including Indonesian leaders have adopted. It is also reflective of a balanced, harmonious outlook that helped create a national identity among a population that comprises 300 ethnic groups and six religions, and resides across 18,307 islands.

As products of such a diverse culture, Indonesian leaders tend to be able to cultivate relationships, find synergy in differences and foster close ties between team members, whether foreign or local. In a 2011 study, Dr Hora Tjitra, Associate Professor at Zhejiang University, argued that Indonesian leaders tend to be characterised by a consultative and soft-spoken approach, where displeasure is expressed in a calm, controlled manner and emphasis is placed on soliciting input from team members.

The nation’s openness to diversity makes the country an attractive destination for expatriates, and Indonesia is increasingly becoming a hotbed for foreign direct investment and human capital inflows. However, the inclusive approach that has worked well within the archipelago to date might become less widespread, as Indonesia increasingly becomes a player on the global business scene.

Maintaining harmony will take on whole new dimensions as the interweaving patterns of ethnicities in Indonesian society are further complicated by the addition of international cultures. For Indonesian leaders, results-orientated outcomes are not widely regarded as an important function when compared to harmonious team building. Goals are set, but they are not used as strict benchmarks with which to reward or penalise.

This might not sit well with employees from other cultures who are used to a culture of goal-orientation, accountability and management by objectives. For expatriates, who value directive leadership, harmony is less about relationship building and more about the setting of clear objectives and expectations. Just as Indonesian culture encompasses Chinese, Muslim and Javanese influences, business leaders in Indonesia need to marry their personal preferences for familial ties and team building, with the more results-driven expectations of their foreign colleagues.

The scope of management in Indonesia is expanding from the 300 Indonesian ethnic groups to include human capital inflows from Europe, the Americas and the Middle East. Indonesian leaders now managing foreign talent will do well to apply nrima, but also to adopt Western practices in order to build harmony and leverage diversity.

Globalised local talent

Yaya Winarno Junardy is President Commissioner of Rajawali Group, one of Indonesia’s biggest conglomerates with interests in telecommunications, hospitality, construction, retail and transportation. The former CEO of IBM Indonesia, Junardy is an example of the ‘globalised’ Indonesia business leader.

Growing up in a village in East Java, the young Junardy was exposed to two different cultures – Chinese and Javanese. Spending over 25 years at IBM introduced him to diverse Western and Asian practices as he worked in Hong Kong, New York, and Tokyo. This shaped a culturally open leadership style that enabled Junardy to move up the corporate ladder at IBM.

One Asia, many ways of leadership

Chinese, Indian and Indonesian ways of leadership have their roots in vastly different religious and cultural heritages. From the Confucianism-inspired philosophies of Chinese leaders, to India’s unique blend of management qualities formed by a national history of necessity-driven innovation, to Indonesia’s complex balancing act of cultures and ideologies, Asia might just be the world’s most diverse continent in terms of leadership styles.

Yet, a common theme is shared between all three leadership traits. Each culture values the community at large. Just as Asian corporations are increasingly investing in corporate social responsibility, Asian business leaders have always considered public stakeholders in their decision-making and value their views deeply.

With perhaps the region’s greatest depth of talent, leadership continues to evolve in China, India and Indonesia. Concepts such as guanxi and jugaad are increasingly well known in business management, but there are complex concepts of thinking and leadership in all three countries that have yet to be fully explored. As these nations play an ever-increasing role on the global economic stage, understanding their business leaders’ needs, drivers and motivators will become a critical aspect of engaging with Asia. With the world becoming increasingly globalised, the diversity of cultures and leadership styles Asia brings to the table could also create entire new possibilities of synergies and mutual learning.

The Asian Ways of Leadership Workshop In November 2012, Singapore Management University and the Human Capital Leadership Institute staged the Asian Ways of Leadership Workshop, which brought together academics and corporate HR practitioners from all corners of the region. The focus of the workshop was to unearth leadership trends, differences and commonalities between those found in the diverse cultures of Asia – including China, India and Indonesia. While on paper, all three nations bear similar traits – including similar rates of economic growth and an emerging middle-class that is rapidly increasing its per capita purchasing power – vast differences in their approaches to human capital leadership exist.

This article was first published in HQ Asia (Print) Issue 06 (2013)