Ideas are the lifeblood of innovation. While many businesspersons hold a view that new ideas are generated by geniuses, the view in Tata has been that innovation goes beyond the solitary genius or confines of traditional corporate research and development (R&D).

Innovation should leverage a company’s internal core expertise, whether that is market research, marketing, engineering, R&D, manufacturing or distribution. It should combine with external sources of expertise, be that customers, vendors or suppliers, academia, and even competitors, in order to develop new products or services. Innovation today is therefore not limited to R&D and product invention. On the contrary, Tata today is trying its best to make innovation part of its DNA.

The process of making innovation an integral part of an organisation’s DNA requires a willingness to accept creative failures. Typically, organisations are taught to avoid anything that is deemed a defect or an error, in order to achieve optimum performance. Mistakes, therefore, are seen as failings that need to be minimised. Typically, an executive’s reputation and reward are based on mistake-free operations and not on the notion of learning from failures.

With this in mind, the Tata Group Innovation Forum (TGIF) introduced an award, entitled Dare to Try, in the company’s annual recognition programme on innovation. The award is given to teams that make an unsuccessful, but audacious, attempt to innovate.

The award received sceptical response in its first year, as the contesting teams were, at first, hesitant to share their failures. However, over the last few years, the perception of this has changed and the number of teams that participate have increased manifold. Yet, the purpose of the award is not to encourage teams to fail. It is simply to encourage those who, ordinarily, would cease to try after experiencing a setback.

The Dare to Try award was introduced in 2007 and, coupled with other TGIF categories, now amasses over 3,000 submissions, from more than 75 separate Tata companies, annually. Whilst the number of submissions is now in the thousands, TGIF scrupulously monitors the quality of each project to ensure consistency and utmost rigor. Plus, in a bid to make the award global, the programme’s early rounds are staged in various cities throughout the world, including Singapore, Bangkok, London, Shanghai, Boston, and Johannesburg.

A recent nominee for the Dare to Try award included a plastic door for the Tata Nano car, which successfully passed all the safety tests, but could not go into production due to consumer perception issues. Other nominees have included an attempt to create self-cooling tiles for buildings and the search for a low-cost drug used to cure visceral leishmaniasis — one of the developing world’s more prevalent diseases.

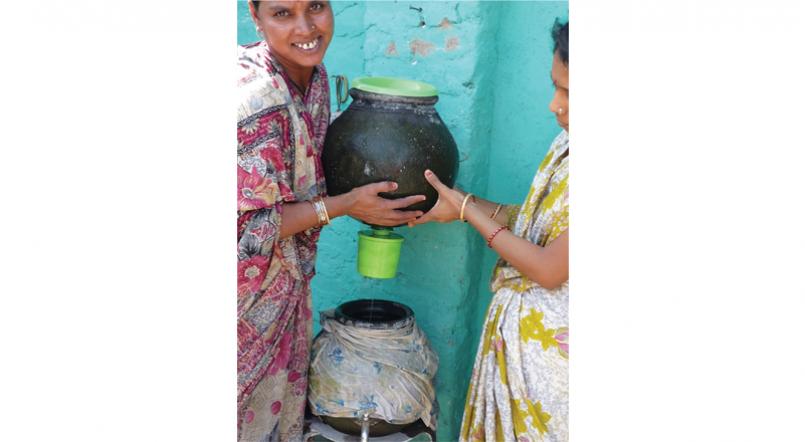

Demonstrating the use of setbacks to achieve final success can be seen in Tata Swach — the low-cost water purifier that began its journey in the laboratories of Tata Consultancy Services (TCS, an IT-solutions company of the group). After several setbacks and early R&D successes, the product finally met standards set by America’s Environmental Protection Agency. This spirit of experimentation led to several innovations and patents being filed, including the use of nano-coatings in rice-husk ash — a plentiful substance in India — to ensure the efficacy of purification.

Within a year of its launch in January 2010, the business was able to sell close to half a million purifiers, making it one of the fastest-selling purifiers in India.

Tata’s Swach: An insight into innovation

Tata has dealt with many technical challenges and opportunities in its history, but the issue of fostering innovation has always been a core focus. While the following may be largely anecdotal, the experience enriched us greatly during the development of Tata Swach. Below are the key insights into what made Swach successful:

- Innovation is a process of discovery.

Experimentation has a value; even if seems like wasted time. The initial design of the Tata Swach was based on the fitting of a cartridge onto an earthenware pot. The team spent much time understanding how to make a hole in the pot without damaging it. However, the final design used a plastic container. Still, the process of trying to make the cartridge fit the pot played a key role in the development of the Swach’s design.

- Understanding “who is the customer?” clarifies what one can do.

The team leader plays a vital role in this task: We spent vast amounts of time with potential customers, working out the product deliverables. We realised that the majority of our customers would not have access to electricity and running water, which became key aspect of our product design.

- Defining “The Cause” unleashes powerful collaborators and talent.

This shifts the attention away from the product itself. Tata defined our business as a pure-water mission, not just as a water purifier business. Safe drinking water is a basic human need that has remained unmet in many parts of the world. The statistics around it make for shocking reading: It is estimated that, at any given time, half of the world’s hospital beds are occupied by people suffering from water-borne diseases. According to UNICEF, an estimated 400,000 children in India die every year due to diarrhoeal diseases spread via impure water. A mere 6% of all urban Indian households use any kind of water purifier, and less than 1% in rural India do so. This urge to help people fuelled our teams’ enthusiasm beyond financial gain, as researchers and other involved parties derived a sense of meaning from this cause.

- When confronted with an 'either/or' situation, choose 'and'.

During initial stages of design, the team was presented with a choice of performance or cost. We unequivocally chose the highest performance at lowest cost. We also had to prioritise between cost and product design (the look and feel of the product). This led us to deeper understanding of the impact of product design.

- A low-cost product does not mean sub-standard look.

Tata Swach was created and designed for consumers, thus design and aesthetics were considered to be important aspects of the product. Acknowledging the lack of in-house expertise, the team roped in an award-winning designer to work on the aesthetics of the product. The look of Tata Swach also evolved significantly through consumer feedback. In fact, the product’s overall appearance has helped it to gain quick acceptance by consumers. To facilitate distribution and delivery, the Swach was also designed to be more stackable, hence reducing logistic costs. With all this input, it should come as no surprise that the Swach’s design netted several awards, such as the Design of the Decade award 2010 and the iF product design award 2010.

- Technology can reduce costs and enhance product performance.

Unlike most other products on the market that are generally halogen-based, Tata Swach involves work in modern chemistry — technology and design similar to nanotechnology is used to purify water. In fact, Swach is one of the first applications of nanotechnology to be adopted for a low-cost product.

- Leveraging locally available materials for innovation.

This, in fact, determines the innovative qualities of a product and its impact. Tata Swach uses a material called paddy-husk ash as the substrate. Paddy-husk ash is made from widely available natural waste, and forms the base over which nano-silver particles are impregnated. Apart from being mesoporous, paddy-husk ash also helps remove colour and odour from impure water.

- A small, capable, empowered team works the best.

Team members should also have direct line-of-sight to the team leaders, whether that is the Business Head or the CEO. More than money, teams need engagement from the top. Hence, there is a need to focus on resourcefulness rather than on resources alone.

This article was first published in HQ Asia (Print) Issue 03 (2012)