Corporations around the world understand the need for innovation in an increasingly competitive environment. What is less well-understood is what organisations can do to spur innovation. On one hand, some rely on extrinsic rewards such as money because they are simple and easy to measure and implement. On the other hand, others argue for the importance of intrinsic motivation.

These people reason that money cannot replace – and may indeed undermine – one’s intrinsic motivation to innovate. Which serves as a stronger catalyst for innovation: intrinsic motivation, or extrinsic rewards? A recent study by a team of Chinese and Spanish researchers (Yu Zhou, Yingying Zhang and Angeles Montoro-Sanchez in 2011) attempt to answer this question. They found that, even in China where people tend to place more focus on financial rewards, excessive use of money can kill innovation. However, when intrinsic motivation is already in place, monetary rewards actually foster innovation.

The case for extrinsic rewards

Many philosophers and psychologists believe that people’s behaviours are changeable and that external rewards can bring forth such transformation. For example, Robert Eisenberger’s studies in 1997 indicated that higher compensation correlates positively with increased innovative behaviour by employees. Long term incentive plans, team-based rewards such as profit-sharing plans, and security benefits were found to bring similar effects.

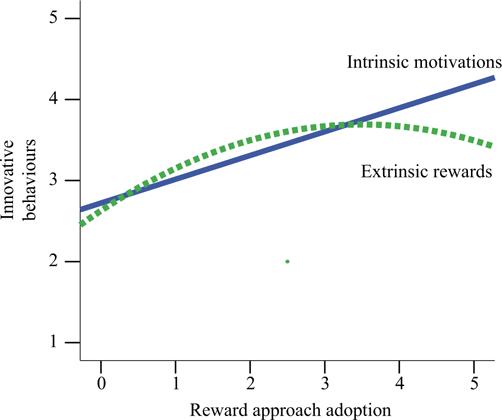

Indeed, Zhou, Zhang and Montoro-Sanchez’s research revealed that external reward is positively related with innovation. But the positive relationship between external rewards and innovative behaviour is not a linear or straightforward one. The relationship eventually follows an “inverse-U” shape. That means, at some point, money will erode the motivation of employees towards creativity and reduce their innovative behaviour.

On the contrary, other psychologists emphasise that nothing is as powerful as the internal desire to innovate. Psychologists have long warned of the “over-justification effect”. In other words, providing extensive incentives for tasks that are inherently enjoyable can lead to a reduction in intrinsic motivation. For example, in 1976 David Green and his colleagues found that rewarding children with certificates and trophies decreased their intrinsic motivation in playing math games.

Thus, advocates for this intrinsic motivation approach encourage practices that foster an employee’s innate drive for innovation. Examples of such practices include:The case for intrinsic motivation

-

Setting achievable targets for innovation

-

Providing extensive learning opportunities

-

Assessing and recognising innovation

The results of Zhou, Zhang and Montoro-Sanchez’s research supports this proposition. Practices that foster intrinsic motivation lead to consistently more innovative outcomes. The impact of these practices is also stronger than that of external rewards.

The best of both worlds?

Well-known innovative companies such as 3M and Google seem to understand the power of intrinsic motivation as well as how to best sustain this motivation: It is not a question of intrinsic motivation versus external rewards but rather how to combine the benefits of both. Zhou, Zhang and Montoro-Sanchez’s study indicates that the best return on innovation occurred when internal motivation was already established, and subsequently reinforced with extrinsic rewards. In this way, extrinsic rewards serve to entrench rather than erode intrinsic motivation. This suggests that sequencing of external rewards is important.

In addition, the researchers found that not all external rewards and internal motivation will achieve the same effects. Out of the five external rewards approaches that were tested, base-salary increases and long term incentive plans such as stock options have the most significant positive effects on innovation. This implies employees seem to appreciate long-term and sustainable rewards better than short-term ones.

Intrinsic motivation also has its own story to tell. When the researchers examined nine factors, only four proved to have a strong impact on employees’ innovative behaviour. They were: setting clear objectives for innovation; recognising innovation; job empowerment and flexibility; and, maintaining interpersonal relationships among the employees.

Google – one of the most respected companies in the world for its innovative ideas and products – is a fine example of appropriately applying these approaches and succeeding. Google’s often-admired but rarely-imitated practice is the ‘20% rule’. This allows employees a chance to spend a significant portion of their time pursuing their own ideas. This initiative has inspired many innovative ideas. Examples include Gmail, Google News and Google Earth.

What perhaps lesser-known is Google’s compensation strategy. Google does not have a reputation for offering the highest base salary to their employees. However, their employees enjoy other benefits such as free food, free laundry, and free health and dental care. In return, Google expects its employees to set audacious goals for each quarter and push themselves hard, because “achieving 65% of the impossible is better than 100% of the ordinary”. This attitude, to achieve the impossible, has reaped great results – Google report that each employee had brought US$336,297 in profit in 2010.

Money may make the world go round, but its impact on innovation is less impressive. It can sustain the flame of innovation, but the initial spark has to come from within.

Methodology

Yu Zhou (Renmin University of China), Yingying Zhang and Angeles Montoro-Sanchez (both from Complutense University of Madrid) sought to understand the relationship between a reward system and employees’ innovative behaviour. They randomly surveyed 300 employees randomly of 18 organisations in the telecommunications industry in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Jiangsu and Zhejiang. The survey was redesigned after an initial small-scale test with 60 questionnaires in the Beijing area. Data was collected via different channels: face-to-face, email and traditional mail. In total, they received 216 valid responses equally spread between males and females, dominated by relatively young workers (81.2% age below 40), who are highly educated (91% has bachelor’s degree and above), and have reasonable work experience within the organisation (54.2% has worked for more than one year). They examined:

-

five extrinsic rewards (base-salary increases, performance-related bonuses, incentive plans for teamwork, stock options and other long-term reward plans, and security benefits); and

-

nine intrinsic motivation factors (enriching job definition, setting innovation objectives, assessing innovation results, recognising innovation behaviours, tutoring performance improvements, providing learning resources, job rotation, self-optional benefits and maintaining interpersonal harmony)

Source Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., & Montoro-Sanchez, A. (2011). Utilitarianism or romanticism: The effect of rewards on employees' innovative behaviour. International Journal of Manpower, 32(1), 81-94.

This article was first published in HQ Asia (Print) Issue 03 (2012)