Japanese companies have recently been highly active in acquiring foreign companies and expanding their overseas operations. Mergers and acquisitions of foreign businesses set new records for the fiscal year 2011-12 with regards to value (US$92 billion) and quantity (474 cases), according to M&A consultants RECOF Corporation.

There are strong reasons driving this boom in overseas investment. These include little growth projected in Japan and the prospect of long-term population decline. High-growth Asia and other developing regions are becoming increasingly important markets. In support of this, Japanese corporations have an abundance of capital, with approximately US$ 2.5 trillion on hand. In addition, the appreciation of the Japanese yen has further fueled this expansion.

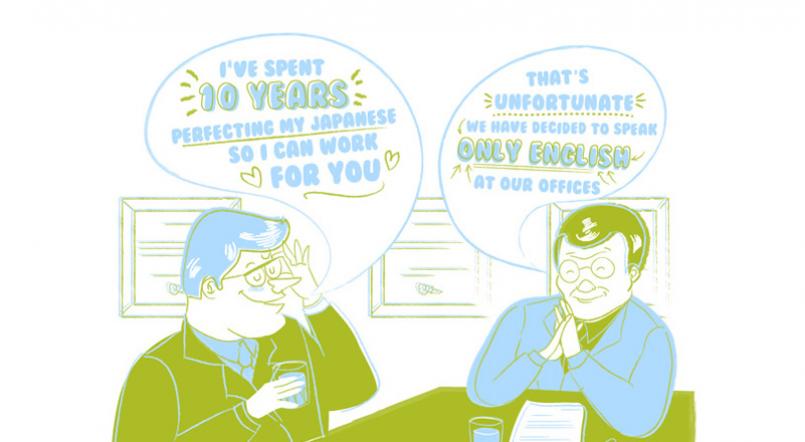

"I've spent 10 years perfecting

"I've spent 10 years perfecting

my Japanese so I can work for you."

It is helpful to remember that Japanese companies have a history of overseas investment. In the 1990s, manufacturers like Toyota, Honda and Sony built manufacturing and assembly plants across the globe. But, apart from these well-known examples, many of Japanese overseas investments then ended in failure. A lack of understanding on how to manage globalisation is widely attributed for this. Quite simply, many Japanese companies failed to adapt their management style to handle global operations.

Two decades on, what is of interest is the broad spectrum of Japanese companies that are now looking to go global. And, these include companies that have traditionally focused on Japan’s domestic market.

An example of this can be seen with the Kirin Beer Company, which recently acquired Brazil’s third largest brewery company Schincariol for US$3.8 billion. Likewise, Terumo Corporation – a major Japanese medical devices manufacturer – recently acquired the American company CaridianBCT for US$2.6 billion.

Today, the ability to manage diverse workforces is even more critical. The growth in Japanese overseas investment is no longer only in manufacturing and assembly. Instead, Japanese companies are looking to internationalise R&D, logistics and marketing capabilities.

The success of Japanese companies will depend not just on product quality and price, but also the ability to drive an international business strategy and create corporate cultures that work across diverse markets. Companies that fail to do this well will pay a heavy price.

Nippon Sheet Glass (NSG) is a cautionary tale. Aiming for growth in foreign markets, they acquired the British company Pilkington in 2006. In 2008, it selected an English CEO from Pilkington, introduced a committee system for corporate governance, changed its accounting to meet global standards, and otherwise seemed to adopt every appearance of transformation into a truly global corporation.

However, NSG soon fell into turmoil, with the English CEO resigning after 15 months. They appointed an American as the new CEO, but he too quit after a short time.

So, what went wrong? First, the communication of ideas between Japanese and non-Japanese managers was lacking. Second, the governance structure was not ideal. Non-Japanese managers were placed in charge of operations but Japanese executives were closely supervising, as well as running the executive nomination and compensation committees. NSG top executives had little prior experience in running global companies, and they severely underestimated the challenges inherent in cross-border M&As.

By rushing ahead with the acquisition, and failing to get the basic foundations right, NSG suffered tremendous damage. From 2007 to 2011, NSG’s revenue dropped by more than 35%, and the net profit plunged from US$640 million to a net deficit of US$35 million.

"That's unfortunate, we have decided to speak only English at our offices."

"That's unfortunate, we have decided to speak only English at our offices."

While part of this slowdown can be attributed to the weakening global economy, it is important to note that rivals like Asahi Glass suffered less extreme and protracted declines.

Fast Retailing (FT) – famous for its Uniqlo casual wear stores – serves as a counter example. Under its charismatic CEO, Tadashi Yanai, a strategy of globalisation is currently the company's highest priority. FT’s inspiration itself is from overseas, as its business model was based on America’s Gap.

During 2011, overseas revenues accounted for 18% of the company’s total sales, and this percentage is rapidly growing. Uniqlo’s goal for overseas sales is to surpass its domestic sales in 2015, which is a highly ambitious task at best.

Yanai has taken the bold step of making English the company's official language. This even includes the use of English by Japanese employees communicating among themselves in Japan. This decision may be inconvenient for employees who are used to working in Japanese, but it recognises that in the near future the majority of the company’s employees will be from overseas.

Already, the majority of new college graduates that join the company are not Japanese. In China, for example, the company's CEO is a Chinese graduate of a Japanese university. Yanai's view is that in order to maintain the company's strengths in product quality, production and sales while expanding globally, Japanese employees must be able to express themselves in a more commonly used language.

In general, Japanese companies should not under-estimate the importance of language in their globalisation efforts. At many corporations, communication in Japanese has alienated foreign employees from their participation of certain business activities. As the corporate organisational structure is such that power is centralised in Japan, foreign employees who do not speak Japanese are denied access to the real decision-makers of the company. In turn, this obstructs the promotion of non-Japanese staff to senior positions and consequently deprives Japanese companies of foreign leadership talent.

Yanai recognised that his basic business plan of providing high-quality casual wear at an affordable price, and sold at attractive shops, can indeed succeed outside of Japan. The success of this has been in part due to the full participation of non-Japanese employees.

Already, the majority of new college graduates that join the company are not Japanese.

Takeda Pharmaceuticals – with a history of over 230 years – is an example of this. Led by Yasuchika Hasegawa, Takeda now accounts half of its annual revenues of JPY1.5 trillion (US$19 billion) from overseas. With operational bases in America, Europe, and Asia, the company appears thoroughly globalised.

But, Hasegawa recognises that more can be done.

Traditionally, Japanese executives have made most of the decisions for Takeda's overseas operations, and these have been executed through a Japanese-style management structure.

Yet, its R&D efficiency is low when compared to other major global drug companies, and even in Japan, its anti-cancer and psychiatric drug lines are not competitive.

In a bid to mitigate these weaknesses, Takeda has recently acquired numerous foreign companies. And, in order to make full use of these, Takeda is currently transforming its corporate identity to a more global style.

For example, in personnel management Hasegawa has appointed non-Japanese employees to head the company’s all-important anti-cancer, drug development, and research departments. English is now used in important meetings, such as those held by the Board of Directors, with simultaneous interpretation provided for Japanese participants who are not fluent in English.

"The company's core principles and strategies are now expressed in mediums that people from different cultural backgrounds can fully understand. My advice to fellow leaders is to foster global human resources and make use of diversity," he said.

Extensive power over important decisions is now in the hands of non-Japanese executives. And this is something Hasegawa is particularly pleased about.

Today, many Japanese firms recognise that they must globalise, but are unclear on how best to do this. Companies like Takeda that are experimental with bold internal reforms could serve as an inspiration to others. Globalisation is never easy, but with strong leadership commitment and comprehensive planning, Japanese companies can overcome this challenge.

This article was first published in HQ Asia (Print) Issue 04 (2012).