Visit any bookstore and you will find titles on transformational leadership, authenticity and ethical leadership. Talk to employees of most companies though, and you are more likely hear to about the pervasiveness and damaging impact of destructive leadership. Birgit Schyns and Jan Schilling, respectively from Durham University and the University of Applied Administrative Sciences in Hannover, published a meta-analysis summarising what researchers have found about the outcomes of destructive leadership.

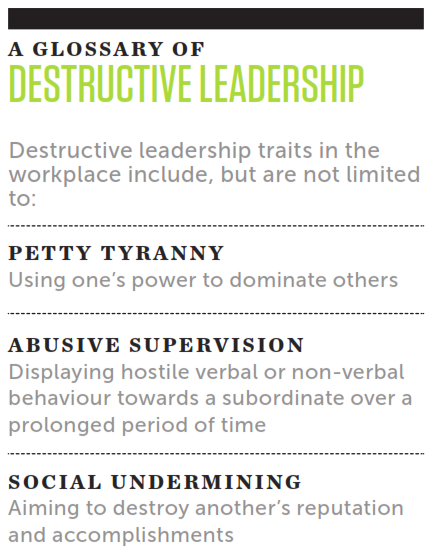

But, what exactly is “destructive leadership”? According to Schyns and Shilling, destructive leadership is a process where individuals are repeatedly influenced by their supervisors in a way that is perceived as hostile or obstructive. Destructive leadership can include behaviours like public ridiculing, scapegoating and giving direct reports the ‘silent treatment’.

The impact of destructive leadership

Summarising the work of 57 previous studies, Schyns and Shilling found that destructive leadership was most strongly related to negative attitudes towards the abusive leader. This is not surprising, as subordinates had strong negative feelings towards destructive leaders. In addition, the researchers also found that destructive leadership was correlated with low job satisfaction and a high desire to quit.

What was more worrying was that the second strongest impact of destructive leadership was to produce counterproductive work behaviour. This suggests that subordinates of destructive supervisors are more likely to act out against the organisation, rather than engage in direct resistance towards the destructive leader. Examples of counterproductive work behaviour include calling in sick when not, bad-mouthing the organisation to external parties and even stealing office equipment and merchandise.

Why do subordinates of destructive leaders act out against the broader organisation? Schyns and Shilling cite several possibilities. First, subordinates may view this behaviour as a safer and more clandestine way of retaliating against their bosses. Second, they may be angry that their organisation has not intervened to protect them from their bosses. And lastly – and most worryingly – these subordinates may have learnt from their destructive supervisors that negative behaviours are tolerated and even endorsed at their organisation.

Mitigating the impact of destructive leadership behaviour

Previous research by Bennet Tepper suggests that abusive supervision plagues an estimated 13.6% of US workers. In Schyns and Shilling’s meta-analysis, the impact of destructive leadership is unequivocal: destructive leadership behaviours lead to negative attitudes towards the supervisor, higher intentions to quit, and counterproductive work behaviours that are directed towards the broader organisation.

But, what can organisations do to mitigate the risks of destructive leadership behaviours? HQ Asia suggest three actions:

1. Acknowledge that destructive leadership behaviours exist

The first step to addressing the problem of destructive behaviour is to acknowledge that it exists. All too often, senior leaders shy away from talking about such topics. Talking openly about the problem shows that an organisation cares, and reassures affected employees that they are not the only victims of abusive supervisors.

2. Develop open feedback channels

It is hard to imagine any organisation would condone or tolerate abusive and destructive supervisory behaviour. The problem is that subordinates of such supervisors are often afraid to report to senior management, for fear of reprisals from their supervisors. As such, it is important for senior management to encourage an open culture where employees can safely share their concerns and report abusive behaviour. Scheduling regular skip-level meetings (where managers meet team members two or more levels below them) can help provide a useful dialogue platform.

3. Develop humane – not just effective – leaders

Many organisations emphasise results, but not the means by which results are achieved.HQ Asia believes that sustainable organisations need to ensure that their leaders are both humane and productive. Organisations should reward leaders not just for achieving business targets, but also for how they develop, motivate and retain their talent. Before making promotion decisions, organisations should collect information on any destructive or abusive behaviours.

This article was first published in HQ Asia (Print) Issue 06 (2013)